Neolithic Man’s discovery, Rodin’s insight, and William of Occam’s wisdom

Shiva as the Lord of Dance (Nataraja) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

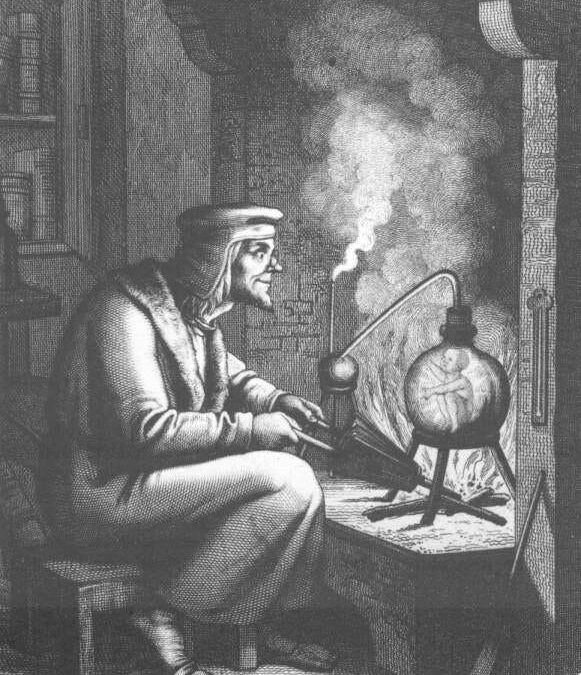

Imagine Mankind’s awe, when, for the first time, he watched a rock melt in a fire, and out ran a liquid. When it cooled, he saw it was different, and he called it metal. It truly was a miracle. Over thousands of more years, curious shamans discovered that other rocks melted, too, and some could be mixed. Some looked green, others grey. Some were brittle when cool, others could be hammered and formed. Some of these rocks were common, like copper, while others like tin came from faraway lands. When mixed, these ancient alchemists looked down into their bubbling cauldrons with wonder to see they had discovered a hard, transformative metal that would change the world – bronze. Poured into moulds, it would cool and would take, and hold, an edge. More importantly for this article, bronze not only pours easily and freely when melted, it expands slightly as it cools, allowing it to duplicate intricate details of a mould.

The Shiva Nataraja

Perhaps the greatest thing for Shiva Nataraja is the ‘lost-wax’ cast bronze with which it is made. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lost-wax_casting). To the faithful, it is the physical manifestation of the divine. In Hinduism, all things come to an end so they can begin anew. Shiva is worshipped as the agent that destroys, ensuring a new cycle can begin. This object is devotional, and it is worshipped. Their cycle of destruction and rebirth involves sound, fury, fire and joy. It is the ideal medium for bronze. At first the metals are smelted, then mixed, and then poured in a prepared clay mould. After cooling, the mould is shattered and the god appears, recreated, reborn!

Detail of the Shiva Nataraja in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

These castings contain many stories of this complex religion. In the left corner of the detail above, the goddess Ganga falls from the sky and is gently caught by Shiva in his/her (a god is beyond gender!) hair, streaming out behind his/her head. Sadly, the Ganges (where Ganga lands and becomes a mother figure and a river) is dirtier today than it was during the Chola Empire, AD 900 -1300, when the best of these castings were first made in Tamil Nadu, in the southeast of India.

Shiva’s wild spray of hair in the Nataraja captures Shiva’s spinning dance of destruction and creation. Shiva crushes a beast underfoot, freeing souls and destroying the world (see picture at the beginning of the article, and below).

Shiva has four arms – one holds a drum, making the sound of creation, one hand touches the fire of destruction in the halo that surrounds the casting, while the other right hand makes a gesture that calms. Shiva’s front left hand, pointing to his raised left foot, signifies refuge for the troubled soul. Shiva will deliver salvation for the faithful. The cycle will repeat itself; it is liberating in its infinite repetitions.

Rijksmuseum, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26605047

Above, we see Shiva lovingly adorned with gold, pink, blue and white cloth. To the worshipper, praying before Shiva, his or her faith animates the divine energy, and Shiva is present.

The Repair

The significance is such that if the image of Shiva is broken, the object may need to be re-cast, requiring the furious fire of destruction and creation, a new hardened clay mould to be re-broken, so that the god can stand forth again in glowing glory. The universe would thus be reborn, the circle repeated, the cycle begun again.

As a team of professional welders1, we were asked to help repair a broken Shiva. We don’t know when the casting was made. We were to minimize further harm to the casting. We did no microscopic examinations, no SEM, EDX, XRD, X-Ray fluorescence and no surface investigation to gauge for soil encrustation or patina characteristics. Although we did no analysis of the materials used in the casting, visually, it would appear to be a lost-wax casting, solid (discernible from its weight), and most likely a copper-tin bronze (likely in the ranges Cu 75-90%, Sn 5-15%, Pb 0-10%, not something rare like a pancaloha Au-Ag-Cu-Zn-Fe casting).

The Fracture

Detail of the broken plug originally inserted into the back of the head to hold the jatta, Shiva’s matted hair

The major break was at the load-bearing point where Shiva’s hair (the jatta) joins the back of the head (above). Examination showed it was not cast or welded in situ, and that the entire hair casting, some 20 pounds, had been made separately and then affixed mechanically. A male plug from the jatta had been inserted in a square receptacle on the back of the head, which subsequently broke at the surface, exposing unoxidized bronze.

Bronze can be welded, brazed, or soldered using MIG, TIG, and oxyacetylene processes, with various lower melting point filler metals. Different strengths are achieved with different processes, and the problems we faced here were (i) the weight of the hair was high, so any repair would requires strength, (ii) we didn’t know what the casting was made of, or how well mixed the ingredients were, their purity or even the porosity and what the inclusions of the melt might be, (iii) the receiving female port is small and thin-walled, and this would exacerbate cracking from expansion from heating or from the aging of the material – and, (iv), most importantly, since copper is highly conductive, the whole casting would immediately heat – potentially burning or at least scorching the patina of centuries. Trying to keep it cool would be nigh impossible.

The Patina

Auguste Rodin, the famous sculptor of such works as the Burghers of Calais, asked his workers not to use the toilet indoors, and to go outside instead and pee on his statues in the garden behind his workshop to speed the patination of the bronzes….

Now while urine is one of the chemicals that can help develop the copper patina of bronze, and even allowing that some may wish to urinate on their less favourite politicians, we would have had to obtain a building permit to build a special scaffold to duplicate Rodin’s method of patina creation, as most of our employees are female. And getting a permit from city hall is time consuming…

What were we to do?

Patina is the accumulated change in surface texture and colour that develops over time. It arises not only from artificial means (see above), but also naturally from air, acid rain, sulfur compounds, carbonates, sulfides and sulfates. The more diligent readers would have noticed a hole in the stand at the beginning of the article (and two in the one below). These holes are for carrying the holy object in processions. In such use, it will be handled and over the years it will collect oils from the hands and lips of the faithful in devotions as well as receiving the residues of incense, candles and flowers. Patina is unique, and of profound significance.

Our literature review further revealed that we were not the first to face the dilemma of attaching the jatta. The picture below shows the rear (and very sensual) image of a Shiva Nataraga with the jatta riveted in position on the back of the head. Alas, a rivet can create a sudden shock, which may be difficult for an aged metal to withstand without shattering.

Obverse of Shiva Nataraga in the Rijksmuseum

Occam’s Razor.

Then I remembered William of Occam. While he is not known for any metallurgical work, being a mediaeval friar concerned with ontology, he is famously promoted for saying that if all other things are equal, the simpler idea is better.

So why arc weld a new bronze plug, involving so much uncertainty and planning to try to achieve the required strength, to avoid cracking, and still have the assured loss of patina? Aesthetically and empirically, the simpler is less risky…

Thus, we chose a piece of oak to be used as a square dowel, cut with an axe’s stroke to run along the grain for increased strength. Yes, we had to chisel out the broken plug and create a new hole in the jatta to mate – but the achieved repair brought smiles from those who cared for their image. And, frankly, there is nothing as pleasant as being thanked heartfully for something you have done well. Indeed, we all want pleasure – as Epicurus noted, saying “we seek the best consequences from our actions.”

Now can you think of a better way of starting a series on welding in The Ironist which has no welding?

—

Contributed by Nigel Scotchmer

My company, Huys Industries Limited, has more than 25 years of experience in manufacturing, assisting the AWS, and representing Canada and the USA at ISO, volunteering at the blindingly dull task of improving worldwide welding standards. At the same time, Huys has received some 20 US, Canadian and Chinese patents in electric spark deposition (ESD) and resistance welding. The German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin said that the boredom of experience can give you the magic of inspiration, or as he poetically put it, “Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience. A rustling in the leaves drives him away.”