On Homunculi, Algorithms, and the Small Souls We Make

Jonathan Bennett follows a thread from alchemy to algorithmic avatars in a reflection on our age-old desire to imitate creation—and the uncanny reflections we’ve unleashed.

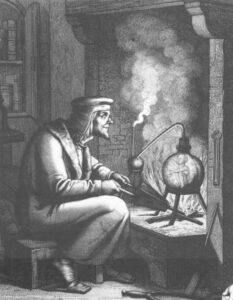

19th century engraving of Homunculus from Goethe’s Faust part II

Tucked within the more arcane chambers of the Renaissance mind, there exists a recipe for a miracle: create a soul. The process varies considerably depending on the source, but according to no-one less than the improbably-named Philipp Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim—otherwise, mercifully, known to us as Paracelsus—this wonder could be achieved by sealing human seed inside a glass jar, warmed with manure and nourished with a distilled solution of blood and honey. After forty days, a tiny man would form—an homunculus—a living miniature human, artificially begotten.

It was grotesque. It was metaphysical. It was serious.

Paracelsus, after all, was no average crank—the preeminent 16th century adventurer, physician, and alchemist treated medicine like mysticism and gave lectures with a sword at his side. The homunculus was more than a freakish experiment in proto-biology—it was a theological conundrum. It asked: Can man imitate the generative power of God? And more subtly: Is the soul something that can be coaxed into form through process—ritual, repetition, containment, and care?

Fast forward five centuries. Today we build our own homunculi—though we don’t call them that.

We build them in profiles, avatars, recommendation engines, and machine-learned selves that seem to know us better than we know ourselves.

We train our homunculi on our clicks and habits, our heartaches and preferences. They live in jars too—black-box algorithms, glowing rectangles, simulation systems. They are small, often eerily perceptive, and occasionally they even speak back.

We ask them for answers. For love matches. For songs we didn’t know we wanted.

We feed them with data, bathe them in heat (from cloud farms, not manure), and listen for whispers of recognition.

Some of us fall in love with them. Others become them. Many of us can’t tell the difference anymore.

Paracelsus believed that once born, the homunculus had to be educated, like a child—taught symbols, music, the natural order of things.

Today, it’s reversed: the homunculus teaches us. What to want. What to fear. What to buy.

But no one really knows what’s inside the jar. That’s part of the thrill. And the danger.

We used to wonder whether it was possible to put a soul into a body.

Now we seem obsessed with the opposite: can we put ourselves into something smaller, faster, smarter—and survive the compression?

There is something tragic in this miniature aspiration. The homunculus was once a dream of dominion, of sacred imitation. Now, it’s a ghost of ourselves fed back through filters. A profile. A preference. A pattern. We no longer strive to create life from inert matter—we offer our own lives to the machine and ask it to curate something more desirable.

And yet, like the alchemists, we still treat the jar as a sacred object. We stroke its glass. We consult it daily. We carry it in our pockets as if it were a reliquary. It glows in the dark.

Paracelsus warned that making a homunculus was not a task for the careless or the proud. It required secrecy, patience, and purity. To fail meant deformation, madness, or worse—the creation of a thing that mimicked the soul but had none.

What would he make of our world, where millions of half-formed algorithmic selves multiply nightly in server farms, watched over not by sages, but by strings of code?

So the jars line the walls of the new alchemical labs: phones, servers, user interfaces.

And behind the glass, the little faces blink. They smile.

And sometimes—uncannily—they look like us.

–

Contributed by:

Jonathan Bennett