If all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy, it makes Jill pretty boring, too. If truth be told, those workaholics Mr. and Mrs. Jack are tedious company, as well. So obsessed has our society become with work, usually paid work, that its antithesis, play, has become a word to relegate to the sub-culture of childhood, to be quickly and thoughtlessly discarded with the arrival of adult responsibility. Yet a moment’s reflection should be sufficient to remind us that play is crucial to a balanced life at any age. Recreation, sport, and drama, all aspects of play involving the exercise of the imagination, are of paramount importance to our quality of life, which is itself of far greater importance than our standard of living, with which it is sometimes, lamentably, confused.

Credit: Pixabay

Rereation is re-creation, rejuvenation, re-invigoration. Because we must work, we need to play. When we play, we not only relieve the drudgery of the working day, but we also release that most creative function of the human spirit, the imagination. And so we play games, read books, and watch shows in order to give it free rein.

The capacity to imagine is most easily seen in children’s play or ‘make-believe.’ They play house, dress up, invite family and friends to imaginary tea parties, comfort invalid dolls, imagine themselves as the nurses or doctors, firefighters, explorers, pirates, or astronauts they think they might later like to be. On the ice or the basketball court, they emulate their sports idols in slap-shot or slam-dunk. They neglect homework to play computer games in which they star as heroes or saviours. In children’s play, the line between the real and the fanciful is often blurred: they have no difficulty in believing that a rabbit with a pocket-watch can lead Alice down a hole to Wonderland, or that behind the coats in a wardrobe is the way to Narnia. My cousins saw no incongruity in mixing model action figures with plastic animals to create a game they called ‘Batman’s Dairy Farm’—as if the caped crusader had time to milk cows or gather eggs! In play, the imagination works out dilemmas often insoluble in real life, or provides temporary respite from them. Charlotte Bronte and her brother Branwell invented an imaginary land called Angria in part as a refuge from the unhappy household their widowed clergyman father presided over. C.S. Lewis and his brother Warnie did the same with ‘Boxen’ and ‘Animal-Land,’ precursors to Narnia. The orphaned Tolkien happily lost himself in the Norse sagas which were later to give birth to Middle Earth, and J.M. Barrie, the boy ‘who never grew up,’ invented Neverland, later the name for Michael Jackson’s home for his own ‘lost boys.’

We never outgrow play. We dress up for Halloween and for masked balls. We play golf, tennis, squash, soccer, hockey and baseball until our knees give out, and shuffleboard, bridge, bingo, and even the lottery thereafter. Most of this play is social and interactive: friendships lasting years develop from it. Even the Harvard undergraduates who invented the ‘social networking’ site Facebook did so as the accidental result of play: geeky young men neglected their studies, seeking to make electronic contact with pretty girls on campus, and stumbled upon an idea to make themselves rich enough not to need to work, or study.

Sport is play. Organized professional sport is also play, mostly because it involves infinitely more spectators than participants, who by identifying themselves vicariously with the player or team to which they have pledged allegiance, can admire from a distance the athletic prowess on display, and share victory or defeat. This identification with the cause of the team has the added advantage, for participant and spectator alike, of diffusing the natural human aggression implicit in competition in an acceptable way by replacing it with a code of sportsmanship marked by handshakes and mutual respect.

The spectacle of young athletes with bodies trained to physical perfection competing on equal terms for a prize or title has a compelling quality that Baron de Coubertin, inspired by the original games held in Greece in classical times, used to formalize the Olympic Games where, every four years, the elite of the sporting world demonstrate grace under pressure in a spirit of friendly rivalry as they push themselves to the limit in feats of apparently superhuman speed, agility, and endurance for the world to marvel at. Can anyone who has seen them perform at the 2008 Beijing Olympiad forget the ‘poetry in motion’ of the swimmer Michael Phelps, the runner Usain Bolt, or indeed any of the impressive performances by Olympic divers, gymnasts, pole-vaulters or jumpers, their exultation in victory or agony in defeat evident to an enraptured audience in televised closeup? Arenas and grandstands alike everywhere erupt with the thunderous applause of a hoped-for victory, spectators all one in their passionate partisanship with the winners, or else they grieve in silent sympathy for those whom victory has eluded. Mika Hakkinen, the ‘Flying Finn’ and former Formula I racing World Champion, once wept openly beside his crippled McLaren car, broken by the tyre-wall into which he had driven following an elementary ‘driver’s error’ he knew he could have prevented. As the hovering helicopter’s camera showed us his private grief, his sorrow became our sorrow.

Competition is instinctive to humanity, and aggression and ruthlessness often regrettably necessary to high achievement in life. It has been argued that these base instincts are channelled and harmlessly diffused by sporting events that in a less sophisticated age would be employed in waging war. Soccer’s World Cup inflames patriotic fervor, it is true, but scores are settled on the playing-field where rules of fair play prevail rather than on the battlefield where they do not, and where red cards are shown, rather than red blood shed; the ‘casualties’ may hobble off the field, but they do not leave widows and orphans.

Finally, play is drama. Shakespeare after all, wrote thirty-seven plays: only scholars or pedants call them works. In watching sports and dramatic productions, the audience undergoes what the Romantic poet Coleridge called ‘the willing suspension of disbelief,’ in which an idealized or fanciful representation of reality masquerades as fact. Does it really matter who wins a race, clears a hurdle, sets a new record, scores the most goals? To argue that it does not is to misunderstand the nature of sport as play. Does it matter whether the deserving young man gets the girl or not, or if the arrogant king learns a necessary lesson in humility, or if the wicked are punished appropriately at the end of the play? To claim that it does not is similarly to fail to grasp the play of drama. For the duration of the performance, the audience is held, daily chores forgotten, entranced by an illusion, voluntarily surrendering the notion that trained actors and actresses are merely pretending to be people very different from their everyday selves, the audience identifying itself with the characters’ joys, hopes, fears, and suffering. Millions do this watching movies and sitcoms on television every night. Very few are the deluded who confuse fact with fantasy after the performance is over. From time to time disgruntled sports fans of the losing side (the word ‘fan’ is, after all, short for fanatic) assault supporters of the rival side. Occasionally children have been reported trying to fly like Superman, sometimes with tragic results, and once, one clearly capable actress playing a ‘loose woman’ on the popular soap opera Coronation Street was attacked in a supermarket while she was shopping by an elderly woman brandishing an umbrella and screaming, “You slut! You hussy!” Such eccentric outbursts are, however, mercifully rare.

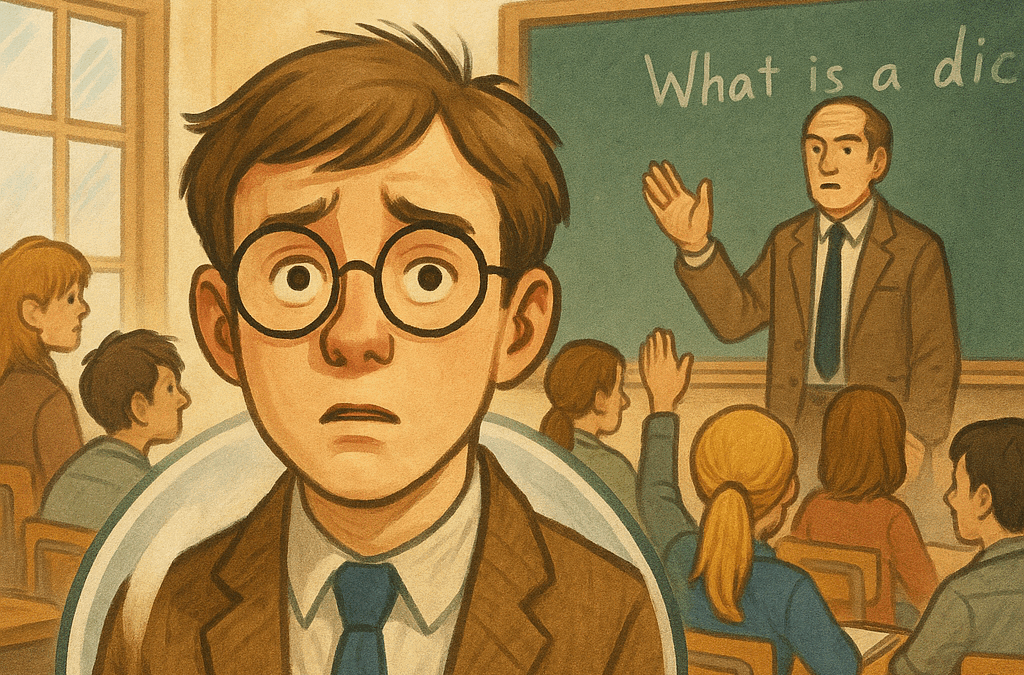

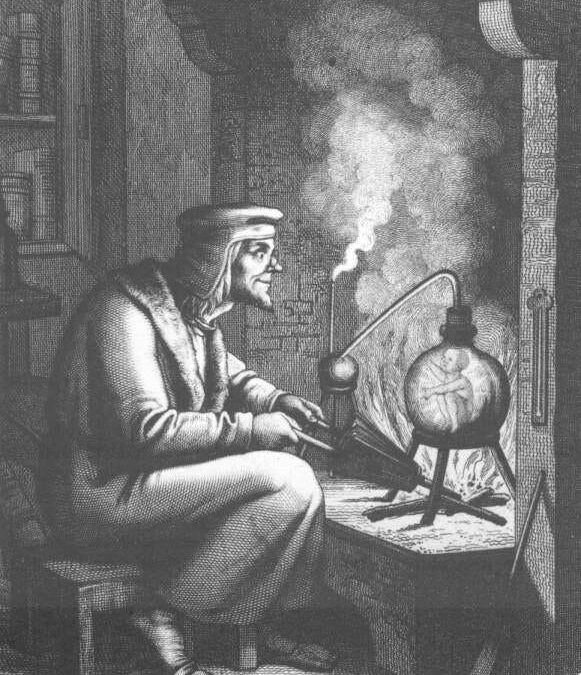

I can vividly remember reading aloud the part of Oedipus in Sophocles’ great tragic drama Oedipus the King to a Grade XIII class more than twenty years ago. I was not Oedipus myself. We were not in classical Greece. But as I delivered the king’s powerful final speech as he emerges from the wings, blind and broken, having realized that he has, in fact, unknowingly killed his own father and slept with his mother, I heard the sound of stifled sobbing from the front of the class. It came from a shy and self-effacing girl who had previously claimed she was “not very good at English.” That she had judged herself too harshly was evident, but what is also clear from the episode is the power of a long-dead foreign playwright to speak across the centuries about the human condition directly to the heart and mind of an Ottawa teenager. People still do and say terrible things without thinking first. This is a matter for tears as much today as it was then. Several years later, I had a similar experience with a Grade XI student writing an Independent Study Unit on Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus. At one point, Faustus jeeringly remarks to the Devil’s henchman Mephistophilis that since the latter has managed to escape from Hell, it cannot be as awful an experience as he has claimed. Mephistophilis replies, “Why, this is hell, nor am I out of it.” To this, Kim reflected in her progress report (and here I paraphrase): “Hell can be wherever we are. We all create our own hells. We can make the best or the worst of our difficulties. I want to make the best of mine.”

Thus play is self-discovery. A memorable play has the capacity to help us understand ourselves. It creates empathy for others. It makes us more understanding of our strengths and limitations. It makes us better people. It amuses, perplexes, challenges, enlightens, instructs. John Palmer says this of Shakespeare: “A politician can find no better handbook to success than the political plays of Shakespeare. Here he can study the flaws of character and errors in policy or practice which may ruin his career… He will find no better instruction anywhere…upon the gentle art of making friends and removing enemies; upon the adjustment of means to ends and of private conscience to political necessity.” Indeed. From Othello we learn of the corrosive effect of jealousy, from The Merchant of Venice the folly of choosing revenge over mercy, from Hamlet the price of indecisiveness, and from King Lear the nature of unconditional love. Ibsen’s plays and those of Bernard Shaw preach earnestly the need to discard outmoded ways of thinking in order to usher in a new age of equity and progress. Comedy’s only serious aim is to remind us not to take life too seriously. We must take time, as the disreputable Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night tells censorious Malvolio, for “cakes and ale.” Oscar Wilde’s absurd Lady Bracknell, played by Brian Bedford in drag, brought the house down in the Stratford Festival’s production of The Importance of Being Earnest a few years ago.

Play is more important to us than is commonly recognized. Shakespeare himself seems to have thought so. In several of his plays, and most memorably in the words of Jaques in As You Like It, he compares life itself to a play: “All the world’s a stage,/ And all the men and women merely players:/ They have their exits and their entrances…” For those of us who can share this lofty actor-director’s view of the purpose of human existence, no more need be said, but for those of us whose more prosaic duty it is to get up tomorrow and head off to the mundane world of work, it is truly good for us to put time aside to play. In fact, it is essential for our well-being and creativity that we do so.

In fact, play can be irony, and ironic, too –