An Ode to Snail

Amidst the splendor of art history, nestled obscurely amongst majestic portraits, mosaic goddesses, and epic battles, an unlikely yet constant character appears time and again: the humble snail. Yes, those slow-moving, shell-carrying creatures have not only glided into the annals of artistic expression, embodying a unique mixture of irony and symbolism, they have also left a distinct trail of whimsy and existential musing. Why do they keep appearing in art throughout recorded history? Unlike more traditional artistic expressions of power and divinity, such as the lion of Ancient Egypt, or Rome’s iconic eagle, the snail’s presence in art offers a contrasting exhibition of quiet persistence, and quite ironically, an undercurrent of defiance. But what exactly is ironic about a snail in art? Let’s delve deeper.

Consider the life of a snail: a creature burdened yet protected by its home on its back, moving at a painstakingly slow pace, and yet, surviving through ages with quiet determination. The irony emerges when this symbol of sluggishness and vulnerability is juxtaposed with states of lavishness, or haste, or mirrors our human complexities and contradictions.

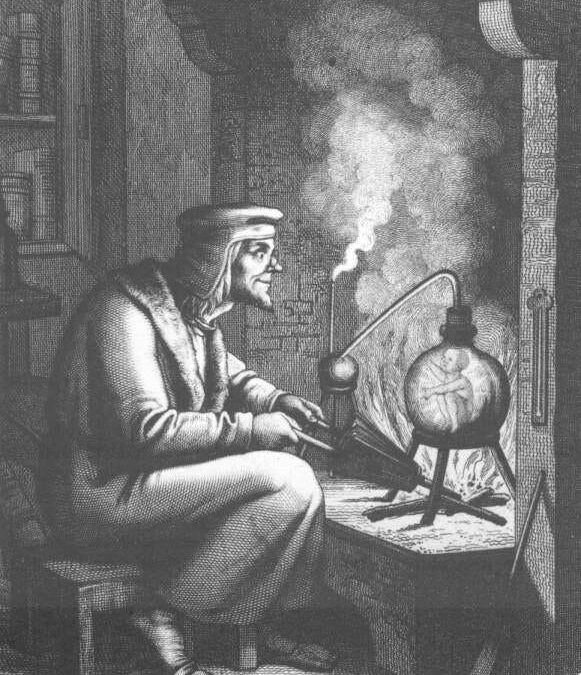

Take, for instance, the medieval fascination with “battle snails” in illuminated manuscripts. Often found in the margins of medieval texts, snails and knights are depicted in engaging scenes of combat, which can perplex modern viewers. These “battle snails” might seem absurd, or humorous, but there is an irony at play that presents a satirical lens on the futility of chivalry, heroics, or inflated egos in medieval warfare. Is there anything more ironic than a creature, synonymous with vulnerability, armored only by its shell, combating a heavily armored knight? This juxtaposition serves to critique, perhaps, the inflated heroics of medieval warriors, suggesting that our glorified battles are as absurd as a snail donning a suit of armor. Take another look at the opening picture above. Is that face on the shield of the knight alive?

Beyond the battlefields of medieval manuscripts, snails in art often symbolize patience and steadfastness. This is evident in ancient mosaics, such as those found in Roman dwellings, where snails appear alongside gods, mythical events, and other domestic and agricultural motifs. These creatures, with their slow but steady pace, symbolize a harmonious natural order, reflecting the values of diligence and resoluteness necessary for personal and agricultural success. The snail’s methodical movement and ability to thrive in many environments make it a potent emblem for endurance and adaptation, and perhaps a gentle reminder to slow down and appreciate the intricate beauty of life in a world rushing forward.

(First image, start of article: Knight v Snail II: Battle in the Margins (from the Gorleston Psalter, England (Suffolk), 1310-1324, Add MS 49622, f. 193v.)

A detail from part of an early 4th century AD mosaic depicting a basket of snails belonging to the floor of the Theodorian transversal hall, Basilica di Santa Maria Assunta, Aquileia, Italy (21410819623)

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

This brings us to the existential pondering prompted by the snail in art. The snail’s slow pace and unassuming presence invite reflection on themes of existence and resilience. Artists like Salvador Dali integrated snails into their dreamscapes, using their odd, slow-moving nature to enhance the surreal quality of their works. Dali’s paintings of melting clocks and distorted figures, and his iconic giant snail sculpture, contrasts the elements of a snail, the epitome of slowness, with the fluid, ever-changing dreamscape that could symbolize a fast-paced, often chaotic world. The artistic expression and symbolism of snails can be a call to slow down, to reflect on our path and pace. Its presence in scenes both imposing and mundane serves as a reminder of nature’s cycles, of growth and decay, and of the small yet significant place each creature—and perhaps each person—holds in the broader scheme of life.

Moreover, consider the snail’s biological quirks: its dual sex and the spiral shell, which always turns to the right, with one exception: the door snail’s anti-clockwise turn, which ironically echoes human dilemmas about identity and direction. In a whimsical twist, the snail confronts us with our own ambiguities and the paths we choose, challenging the viewer to reflect on identity and pace in our rapid world.

So, when you next encounter a snail in the hallowed halls of art history or nestled within a surreal masterpiece, consider the layered ironies it presents. In a culture obsessed with speed and productivity, the snail stands as a testament to the virtues of slowness and contemplation, offering not just a trail of slime, but of irony, compelling us to ponder—slowly but surely.

Dali, Salvador. Snail and the Angel. Bronze, 1984. ArtScience Museum, Marina Bay Sands, Singapore.

Choo Yut Shing, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Contributed by :- Shari Bly