The story is told by his son Dylan of a memorable exchange between Dylan’s father, the Canadian writer William Bell, famous for his novel Forbidden City, and Dylan’s sister Megan. Megan had been reprimanded for some unspecified childish misdemeanour or other, and had retaliated by sending her dad a note which read, “I hat you.” Her father’s response was to give her a note on which he had written, “I glove you.” This is a fine example of what the French writer Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), the author of Madame Bovary, called le mot juste, by which he meant the use of “the exact word” or phrase that best conveys the writer’s or speaker’s thought in a particular context, and does so memorably. The word “glove” emboldened here, like all other examples of other mots justes cited, italicized and in bold throughout this essay, is apt, not only because Dad’s reply is implicitly one of humorous understanding and fatherly forgiveness, desirable qualities in a loving parent, one of whose functions is, after all, not only to correct misspelling, but more importantly, to protect his children from harm or cold, as a glove does one’s fingers, but also because as a writer and English teacher himself, William Bell has made use of a clothing pun, which makes the gentle joke memorable. What effect the reply had on Megan is unknown.

The website Vocabulary contains another example of the mot juste. An anonymous contributor tells us: “My son has always prided himself on employing le mot juste, ever since he was two and announced proudly that he was too selfish to give me a lick of his ice cream.” The use of such a word by a precocious two-year-old to characterize his reason for choosing not to share is remarkable for the lad’s own unapologetic self-knowledge, memorable for this alone.

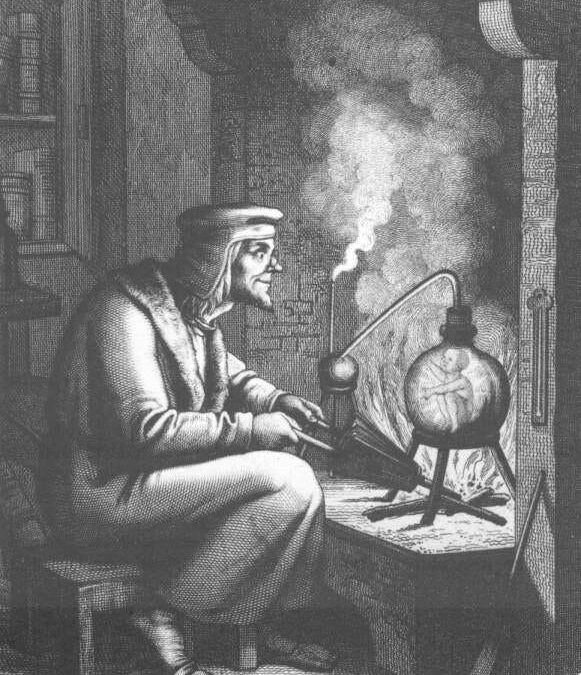

Some jokes rely for their impact on their placement of the mot juste at the end of a sentence. Ronald Reagan’s famous jest about bureaucracy is one of these. Taxpayers , he says, are in fear of the visitor who says, “I’m from the government and I’m here to help.” The joke lies in the assumption that whatever claims governments make about their abilities, they manifestly fail all too often to provide needed assistance. As a child, I was intrigued by the grim humour in an illustration of a medieval woodcut in a school history book in which a man with a long spoon in his hand was pictured sharing a bowl of soup with an evil-looking companion. The caption read, “If you dine with the devil, be sure to use a long spoon.” Make sure you keep your distance from those who cannot be trusted. The mother of a pupil of mine once gave me a plaque with a memorable double entendre now hanging on our library wall downstairs. It reads, “Robinson Crusoe is the only man who got his work done by Friday.” Friday, Crusoe’s companion, is so named because he arrived on their desert island on that day.

I recall my father’s reply when my mother asked why he was so long in joining her in the car during a school Parents’ Night in England decades ago. I had told her that I had seen him talking to the mother of a classmate of mine, Bobby Tether. Dad confirmed this when he re-appeared: “Sorry, I couldn’t get away. I was tethered.”

Examples of le mot juste abound in literature of merit, as you might expect. Playwrights, novelists, and especially poets, earn their reputations as wordsmiths, after all. In his famous two-line poem In A Station of the Metro, Ezra Pound writes, “The apparition of these faces in the crowd: / Petals on a wet, black bough.” The poet is looking down at a crowd waiting for a train in a Paris subway station. What he sees is transformed by an “apparition” born of poetic insight: faces in the crowd below, seem to be “petals” on a “black bough,” presumably because these constitute the multitude waiting patiently for the train, all wearing dark raincoats on account of the day’s rain. Such is the power of metaphor. Ezra Pound was a friend of the great Anglo-American poet T.S. Eliot, who in his celebrated poem The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock chronicles his narrator Prufrock’s awareness of the meaninglessness of his lonely life of cocktail and coffee parties beset with trivial conversations with people briefly met and then quickly forgotten. He says “I have measured out my life in coffee spoons.” His life has been, he tells us, characterized by decorative cutlery: that, he believes, has been the value of his entire life…

Yet another American poet, Randall Jarrell, wrote of the fate of a member of the flight crew of a World War II bomber aircraft in his poem The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner. This young man’s task was to protect the aircraft from an enemy fighter approaching from behind. In a mere five lines, Jarrell powerfully conveys the nature, extent, and significance of the sacrifice this crew member has made in his violent and premature death, summing up in a single word an unforgettable image– a mot juste– of what has remained of him after the attack:

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze,

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

In Animal Farm, his political fable about totalitarian governments, George Orwell describes the perversion of the ideal of “equality” that is the mantra of revolutionary utopians everywhere. After ousting the human proprietors of Manor Farm, the pigs re-name it “Animal Farm”, promising all animals an end to subservience for them. All animals are now to be equal. But all too soon, the promise is amended to read, “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.” The pigs will be privileged, as Party members were in the unlamented former Soviet Union. The other poor animals are dimly aware that the revised slogan is somehow a betrayal of their Revolution, but lack the intelligence to see that one form of servitude has merely replaced an earlier form. You cannot have degrees of equality: you are either “equal” or “unequal”; that is what the words mean. A political system based on duplicity and misuse of language may pretend that conditions for its people have “improved”, but this is mere deception, as are today’s common use of euphemisms such as “passed” for “died”, or “re-educated” used by tyrants to mean “brainwashed.” Orwell’s essay Politics and the English Language makes clear his commitment to truth and honesty in the correct use of words.

In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Scout Finch, who had once assumed her mysteriously reclusive neighbour Boo Radley was some sort of monster imprisoned in his parents’ house next door, finds out at the end of the novel that he has saved her life from a man bent on revenge against her family. Boo comes reluctantly from out of the shadows to meet her for the first time, and she greets him with a characteristic childish acknowledgement, in an understatement that he undoubtedly appreciates: “Hey, Boo.” The reader is instantly reminded of the difference between the monster of the past and the hero of the present. This famous quote inspired the title of a thoughtful documentary film on the novel.

In the English-speaking world’s most popular trilogy, J.R.R.Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Frodo the hobbit reflects on a missed opportunity to despatch the would-be thief Gollum: “It’s a pity Bilbo didn’t kill Gollum when he had the chance,” he tells the wizard Gandalf. “Pity?” replies Gandalf. “It’s pity that stayed his hand.” Gandalf knows that pity, unlike mercy, with which it is sometimes confused, is a double-edged sword, to be used with caution. Not for nothing did Stefan Zweig entitle his novel Beware of Pity, as it may well be the product of mere selfishness, as a close reading of the novel will demonstrate.

Only once in Scott Fitzgerald’s great novel The Great Gatsby does its wisely observant narrator Nick Carraway reveal his judgement of Daisy Buchanan, the beautiful wife of Tom, a privileged serial adulterer. As he is her cousin, he is less likely than others to be seduced, as they are, by the attractions of her great wealth, her physical beauty and bewitching gestures and observations. Nick, normally both discreet and cautious in his judgement of others, nevertheless reveals, near the beginning of the novel, that Daisy’s beauty is “meretricious,” which means it is merely superficial. The word is derived from the Latin, meretrix, meaning a prostitute. By the end of the book, readers come to see the aptness of this adjective when applied to her character, and not to her looks.

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ famous poem Spring and Fall describes the poet’s sensitive young friend Margaret as “grieving” at the sight of falling leaves in autumn. He knows she will want to know why beauty must pass from the earth. Adults know why: it is “the blight man was born for,” by which Hopkins means not the annual succession of the seasons, which we all come to recognize as inevitable, and comfort ourselves with the knowledge that spring and summer will come again. No, he says in the poem’s final line, she is, in her own way, mourning the transience of all life, although at the time she is too young to understand this. All things must pass. You do not know it yet, the poet warns, but “it is Margaret you mourn for.” For the sombre conclusion is that Margaret, like Hopkins, and like you and me, too, dear readers, are mortal, and we will also all pass away eventually, forever, never to return….

Another Margaret, this time the United Kingdom’s first female Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, was a woman of strong convictions who made no concessions to political correctness. When asked to change her mind on a question of principle, she retorted, “The lady’s not for turning,” a pun on the title of a play then popular. For a lady she truly was, in her hairstyle, dress and deportment. When an Opposition Member of Parliament came to ask a favour from her, he was not only denied, but humiliated. He later admitted to his colleagues in a memorable mot juste, “I was handbagged.” No man, needless to say, could have done this to him.

The accolade for the most inspirational use of the mot juste in English belongs to that great orator Sir Winston Churchill, who famously “mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” In his tribute to the Battle of Britain pilots who repelled the Nazi Luftwaffe in the dark days of 1940 and saved the nation from invasion, he declared, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” In fact, his mot juste for these heroic young men has been immortalized: these Royal Air Force pilots are now known as “the Few” decades later. The contrast between “many” and “few” can never have been so properly emphasized.

The Australian writer Anthony McCarten has analyzed in painstaking detail in his book and film by the same title, Darkest Hour, the “timely words, exquisite phrases, superb sound-bites that would have been just as memorable to an audience one thousand years in the past as one thousand years in the future” spoken by Churchill, “who believed in the core of his rather poetic soul, that words mattered … and could intercede to change the world.” Among these memorable mots justes, McCarten detects the influence of such practitioners of rhetoric as the Greek Socrates, the Roman Cicero, Lord Byron, John Donne, Robert Browning, and even Teddy Roosevelt and the Italian Garibaldi in Churchill’s famous 1940 House of Commons speech “I have nothing to offer you but blood and toil, tears and sweat.” Yet these words had the power “to stiffen the sinews” and “summon up the blood” for the fearsome struggle ahead, just as Shakespeare’s Henry V does for his warriors before the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. Mr. McCarten examines another speech of Churchill’s, similar in its dramatic effect on its hearers, one in which his understanding of anaphora, the repetition of a single word of power, reveals itself. Churchill himself, in his History of the English-Speaking Peoples, drew readers’ attention

to a speech by Prime Minister William Pitt in 1800 in which his warning about the belligerence of Napoleon is underlined by Pitt’s repetition of the word “danger” five times in four sentences. Churchill himself, McCarten points out in a quotation from the historian Richard Toye, does the same with “the repetition of (the) word ‘victory’ five times within one sentence (which) created an impressive sense of Churchill’s single-mindedness and determination.” McCarten then details Churchill’s use of ‘we,’ ‘us’, and ‘our’ in order to unify his audience in the face of the threat from Hitler’s “egomania.” The effect of this was “a rapturous response the following day” in the House of Commons. Churchill’s facility with words, later to earn him the 1953 Nobel Prize in Literature, was his great gift to us today. Nazism was crushed, Hitler a miserable suicide, and the Third Reich obliterated. Such is the power of words used well to rouse a righteous spirit to oppose evil. Evil is always with us, and eternally needs to be opposed.

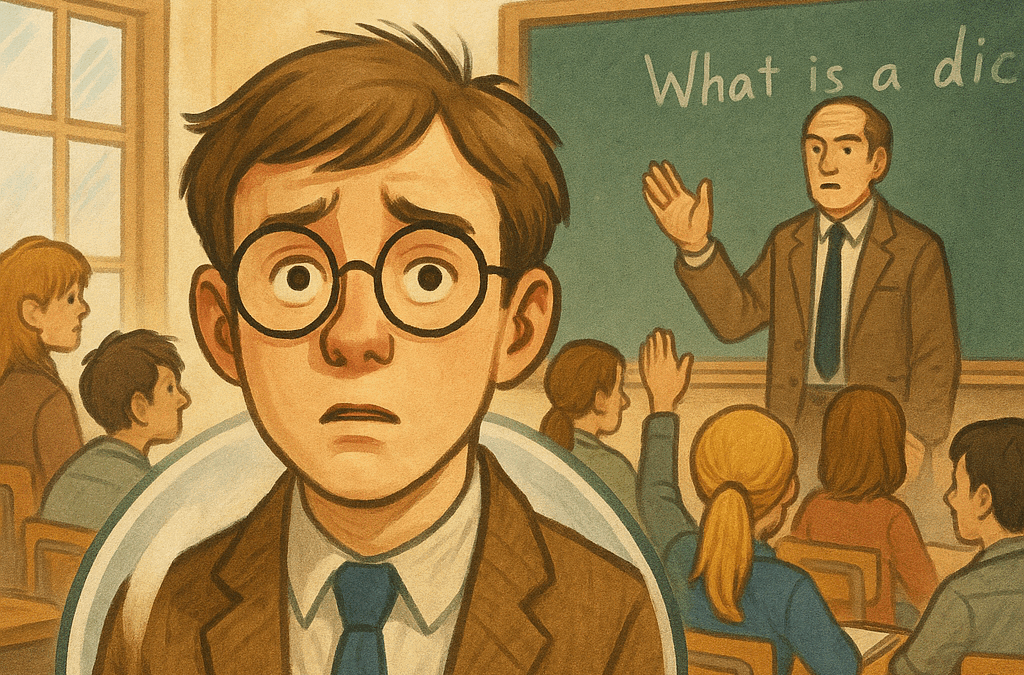

It is thus hard to understand the Ontario education system’s failure to emphasize the importance of le mot juste, and of its unwillingness to see the simultaneous need for the systematic study of etymology, or vocabulary development, of how and why words change their meanings over time, as well as the correct and memorable use of words today, and the study of common errors of grammatical misuse, all of which have been shamefully neglected or ignored by bungling curriculum designers. In too many school bookrooms, the admirable workbook series Words Are Important, to cite but one exemplary work, gathers dust, and the triviality of the frequently toxic “media study” has taken pride of place. “O tempora! O mores!”

(This is an edited version of a talk given at Ottawa’s Friday Lunch and Discussion Club, on Nov. 15, 2024)

Contributed by Peter A. Scotchmer, Ottawa, Dec. 22-26, 2024