Miranda (1875), by John William Waterhouse

Filippa the Flaxen, Queen of East Anglia, with hair like soft strands of warm gold, shimmering in sunlight, the colour of the muted sun, is seldom remembered these days. Once upon a time, though, her people, the Flax, were cultivated and eaten in much greater quantities than today. As a grain, they liked to be eaten. As a people, they had feelings, hopes and worries – just like you and me.

Flax, added to bread, gives a nutty taste, and the cooked dough has a lovely, spongey feel to it. The crumb is regular, and small, and it springs more than a pound cake when pressed – and there are no unwanted calories from butter and sugar! Although it needs longer to rise, and a second proofing, it makes a great bread.

Ground flax seeds are oily, as they are rich in protein and nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids. Unground, the seeds are crunchy. Often, they are added to smoothies, yoghurt or oatmeal. This masks the oiliness, and is an easy way to get the benefits of the grain. Another trick is to grind the seeds more fully, making a finer meal. Others blend flax with stronger flavours and spices, such as cocoa powder and peanut butter.

As you know, in 6th century Proto-Brittonic, the word flax means “nearly hairless in the private parts,” and it is this genetic mutation, most noticeable in the colour and presentation of hair on the body, became both the glory and the bane of the Flax. Early Neolithic scientists in Little Bottom-by-the-Sea first recorded flaxen children amongst the dark-haired Neanderthal tribes of Suffolk in East Anglia. Their published research postulated that it was produced by a recessive allele, Ff for flaxen, based upon studies of the hairy inhabitants of Framlingham.

You will remember Ed Sheeran, the popular singer from that market town, has flaxen-red hair, too.

Flax needs well-drained soil[1], so it did not do well amongst the boglands of East Anglia. This led to the first migrations of the Flax. They moved northwards, towards Scandinavia, and then eastwards as far as Georgia (then Colchis) on the Black Sea. These were the famous ‘spiking’ – quick – attack – burn – and – spread – some – seeds – raids of the Ancient Flaxens. (You remember the Vikings from school? The labial ‘sp’ sound of ‘spiking’ gradually shifted with the Great Consonant Shift, to a labial-dental sound of a ‘v’, becoming ‘viking’[2]). The success of these Flaxen raids can be measured, of course, by the many light-haired peoples of the Scandinavian countries today.

Another aspect of why Flax spread is its great utility. Flax, besides being eaten, is made into linen and its oil into linseed, paints and preservatives. Its fibre is stronger, straighter, and softer than cotton. As the Flax spread east, and down the Dnieper and Volga Rivers, these other properties became more and more important. The Flax made the first composite armour, linothorax (λινοθώραξ), which was made of many layers of woven linen soaked in linseed oil. The oil hardens with oxidation, providing an effective Kevlar-type protection:

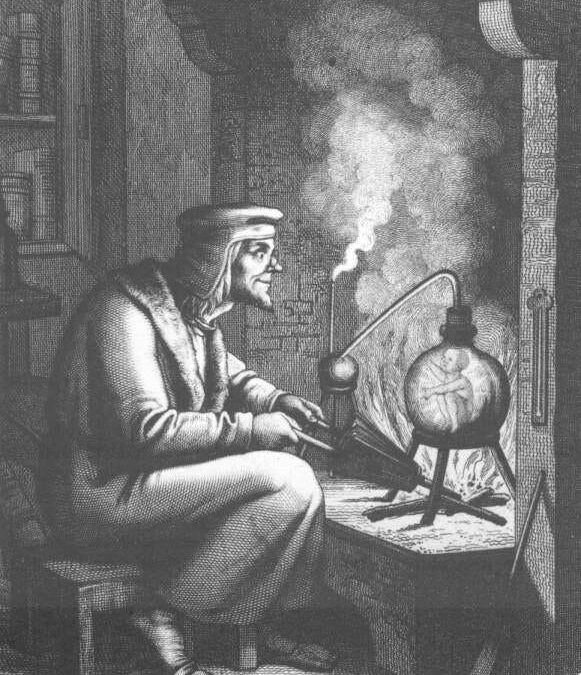

Alexander the Great wearing linothorax armour at the battle of Gaugamela, 331 BC

This armour was used by the Varangian Guard up until the fall of Constantinople in AD 1453.

Filippa, the heroine of our tale today, had other worries, too. As Queen of the Flax, she had to protect her people. She was particularly worried about the excessively libidinous nature of the hairy East Anglians. While they appreciated the beauty of Flax, they were not respectful of their innocence and naivety. This inability to treat women well may explain why these tribes today are largely extinct – but it may also be due to their excessive inbreeding.

They also had over-sized canines which were prized by their enemies for carved art, tools and arrowheads. Their reputation for concupiscence coupled with their over-sized ivories gave us the vulgar term “being horny,” which is still used today.

It is said that the hedonistic and excessive behaviour of the inhabitants of Suffolk attracted the Normans to England in AD 1066 to learn their amatory techniques and skills—an influence that, even today, keeps the French jealous of the English.[3]

Indeed, French jealousy of the English flaxen girl is reflected in literature and music. There is Leconte de Lisle’s poem, The Girl with the Flaxen Hair (La fille aux cheveux de lin), from his Chansons Les Rosbif.[4]

Sitting amidst the alfalfa in flower,

Who sings in the cool morning hour?

It is the girl with the flaxen hair,

The beauty with cherry lips so fair

… I shall dare

a kiss of your crimson lips to steal,

your flaxen locks to caress and feel!

Love, in the summer sun so bright,

Sang with the lark for sheer delight.[5]

For many, Claude Debussy’s clear, light, and impressionistic style musically captures the ideals of beauty:

It was thus understandable that Queen Filippa wished to protect her subjects from the insidious advances of certain types of men. She was involved with the politics of her time; she was well educated, an academic, a family lady, and had even acted as a ‘Berzerker’ leading ‘spiking’ raids. So let’s conclude today’s Forgotten Hero who sought to protect her people not just from conquest, but from poor nutrition and bad decisions with her famous declaration (sometimes incorrectly attributed to Martin Luther), saying, as she nailed it to the main door of Framlingham Castle, “Here I stand, I can do no other:”

o Flax is an aid in losing weight, helping to reduce the risks of diabetes and obesity

o With its fibre, flax is a gentle and natural relief for constipation

o Flax can reduce blood pressure

o And it is a pretty flower; relax, enjoy the simple things of life

A field of flax flowers; they can be white and red, too

P.S. We tend to eat only one grain these days – wheat. For most of Mankind’s history, Man would eat many grains – barley, flax, oats, rye, spelt, etc…surely that is reason enough to add a little flax to your diet?

[1] Flax grows well in the cooler, dryer Canadian prairies.

[2] A labial consonant is produced by using the lips, labiodental consonants by using the top lip and teeth. No one knows why, but from the twelfth century and until the eighteenth century the sounds of the consonants in English changed how and where the sounds were made. One view is that it is a result of poor dental hygiene and a lack of competent English dentists. On the other hand, it might be a lack of chocolate.

[3] In the interest of fairness, we must note that some recent French research suggests there is a connection between the nutty flavour of English Flax and the higher-than-average number of lunatic asylums in East Anglia, with a concomitant increase in overall nuttiness, per capita, in the people, than in France.

[4] The French joke for the British as ‘roast beef’ (Les Rosbif) is both a term of endearment and the subtle recognition of their inferiority to even the hairy East Anglian male.

[5] Sur la luzerne en fleur assise,

Qui chante dès le frais matin ?

C’est la fille aux cheveux de lin,

La belle aux lèvres de cerise.

…Je veux

Baiser le lin de ses cheveux

Presser la pourpre de tes lèvres!

L’amour, au clair soleil d’été,

Avec l’allouete a chanté.

contributed by Nigel Scotchmer