Wherein Jonathan Bennett avoids packing by reflecting on the weight—literal and spiritual—of unread books and overgrown libraries.

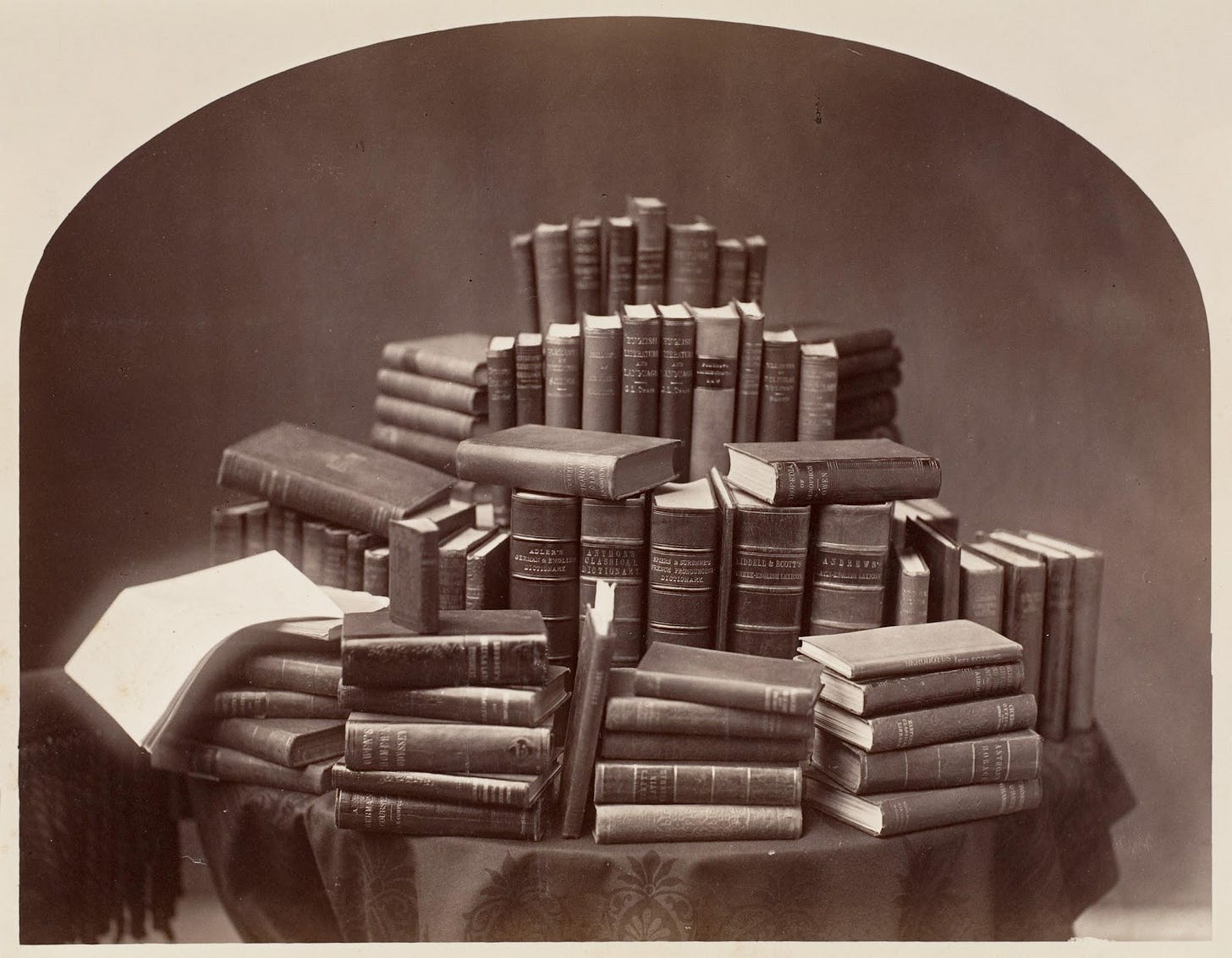

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a man in possession of too many books must, at some point, try to move house. That moment has come for me. As I stare down the unyielding walls of shelves, boxes, and precarious floor stacks—some of which seem to be structurally load-bearing—I begin to suspect that I have not, in fact, built a library, but rather constructed a burdensome shrine to forsaken intentions.

Book collecting, I now realize, is not a hobby but a lumbering epistemological problem. Why, in an age where the breadth of human knowledge lies but a tap away, have I encumbered myself with the complete works of one Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin? I don’t recall purchasing them, and I certainly don’t recall reading them. But there they are, in thirteen sturdy leather-bound volumes, radiating ideological menace from beneath an assortment of Greek comedies in cheap paperback (I wonder how Aristophanes likes his moustachioed neighbour).

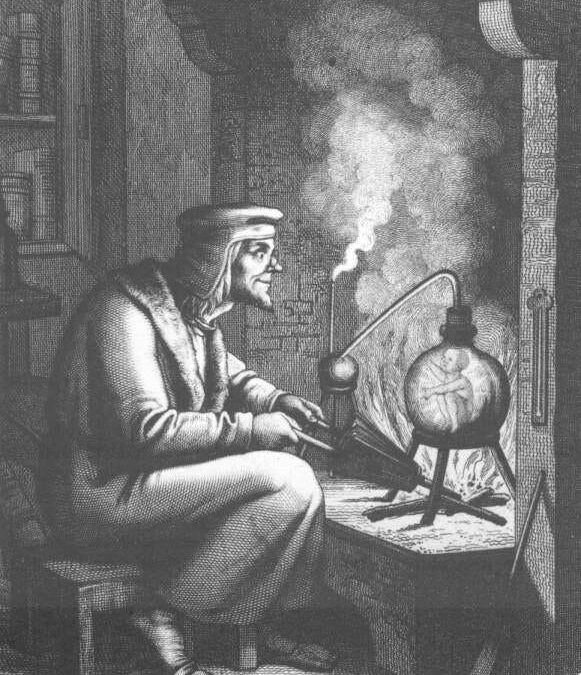

They’ll have to be packed. Of course they will. Along with Abbas Milani’s ponderous biography of the Shah of Iran, which I started in 2014 and never got past the preface (I was distracted by a sudden desire to reread The Brothers Karamazov, a book I’ve also never actually finished). And then there’s Athanasius Kircher’s Oedipus Aegyptiacus, a tome so dense and esoteric it may, in fact, be sentient. I like to keep it visible on the shelf to intimidate visitors. No one’s ever asked to borrow it, which is just as well.

The real problem, of course, is weight. Books are made of ideas, dreams, and knowledge, yes—but also of pulp, glue, and cruelly sharp corners. As I lug yet another box labelled “Misc. Theology & Light Occultism” (inside: Ficino’s commentaries on Dionysius the Areopagite, Eliade’s Forge and Crucible, and a surprisingly heavy volume called The Mirror of Celestial Harmonies, which I’m 60% sure does not actually exist), I begin to ask myself the question no bibliophile wants to face: why do I keep buying these?

It’s not for efficiency. Google can tell me anything I’d like to know—provided I want a badly paraphrased summary from a site last updated in 2008. But Google doesn’t smell like aging paper. It doesn’t carry the haunting marginalia of a previous owner who underlined every instance of the word “light” in Pseudo-Methodius. It doesn’t weigh eight kilograms and sit on your desk like a judgment. These are things only books can do.

Take, for example, the Brill-published Encyclopedia of Western Esotericism. It cost the equivalent of a long weekend in Florence and has the mass of a dying star. Do I read it? Not really. But do I browse it, consult it—perhaps in a bathrobe while sipping scotch, just to check if it has an entry on a dream I once had involving John Dee? Admittedly, on occasion.

Some books serve a purely decorative function. My beautifully bound edition of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire gleams with the sort of gravitas only 19th-century typography can provide. I’ve cracked open a volume maybe five times. But I own it. It exists. I can point to it and say, “That is part of my intellectual landscape,” which is more than I can say for most of what passes through my browser history.

Other volumes are more intimate. My battered single-volume Lord of the Rings, spine cracked and flaking, has followed me since I was ten. It’s unreadable now—half the pages are loose and it smells faintly of basement—but throwing it out would be an act of sacrilege. Same goes for my copy of Panofsky’s foundational Studies in Iconology, last opened during an undergraduate panic attack and now mainly serving to stabilize the behemoth Oxford Dictionary of Wine, itself wine-stained and therefore possibly the most honest book I own.

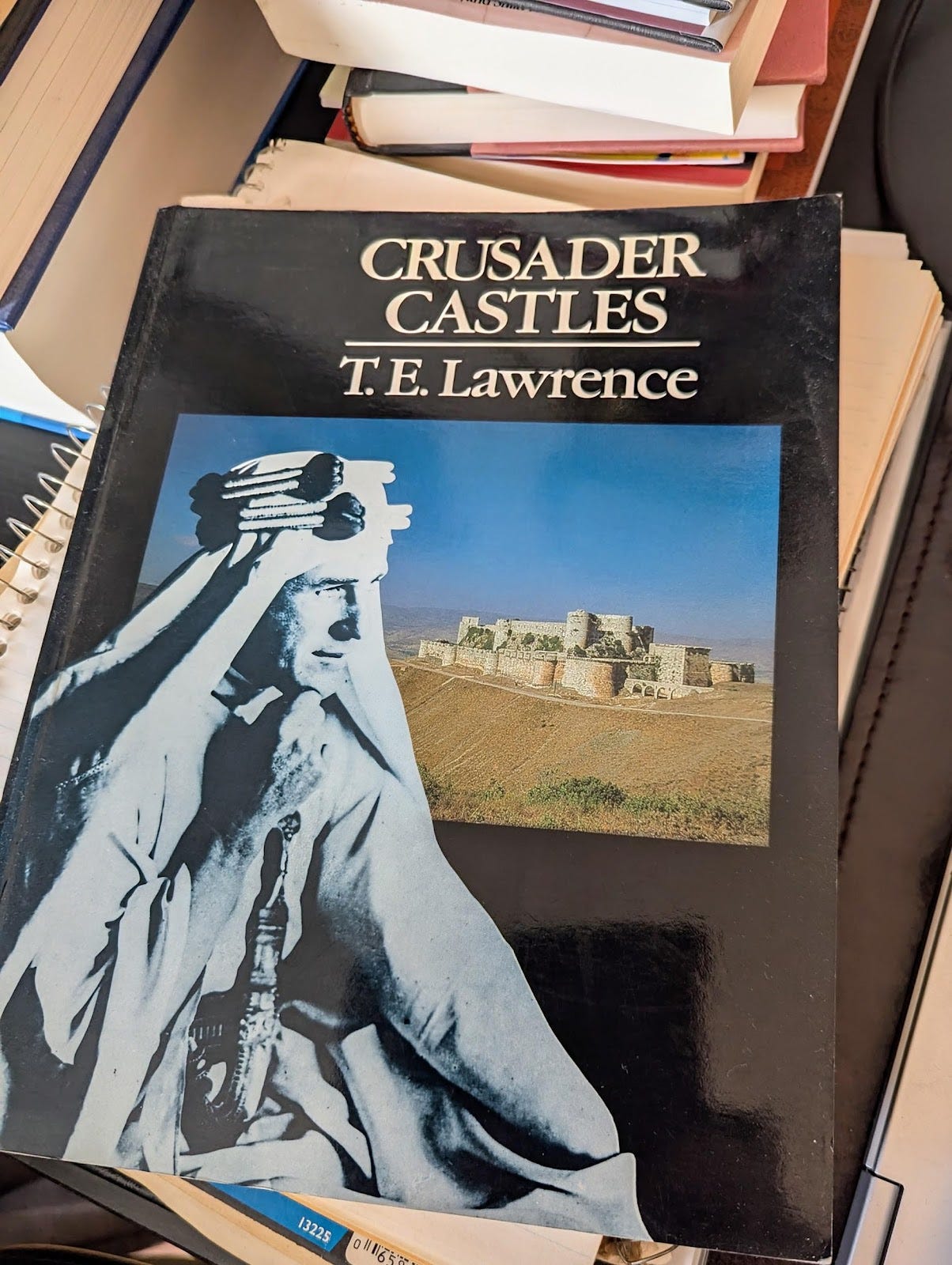

Some books are nostalgic anchors—souvenirs pressed into hardback. My history of Istanbul is still bloated and wavy from having been dropped in a fountain, its margin notes stained by coffee and pastry grease. The cover of T.E. Lawrence’s well-thumbed Crusader Castles features the very same photo I took of Krak des Chevaliers, making it feel less like a book and more like a private handshake across time. The travel guide to Tbilisi I ordered off Amazon turned out to be just a printed Wikipedia article—later reused to write a shopping list. From Vienna, sumptuously illustrated German-language catalogues for the Kunsthistorisches Museum and the imperial Schatzkammer—glorious, unread, and far too beautiful to throw out. And in the midst of it all, a hefty Spanish cookbook purchased in Seville, quietly proving that not everything in my library is theoretical.

Some acquisitions are harder to justify. Montague Summers, for instance—yes, the full collection. Did I need his baroque ramblings on witches, vampires, and demonology? No. Did I want them? Kind of. But something deep within me whispered: “You’re the sort of person who should own this,” and I obeyed.

The same voice once insisted I needed Mad Princes of Renaissance Germany and The Pope’s Elephant (a surprisingly moving account of a pontifical pachyderm that, frankly, deserved a better fate). Together with three different biographies of Emperor Rudolf II, the Secret History of Procopius, and Chronicles of the House of Borgia by Frederick Rolfe under his alias as Baron Corvo, they occupy a shelf that I’ve mentally categorized as “Unhinged History.” Incongruously wedged at the end is my emergency copy of The Stand by Stephen King—because, apparently, even in an apocalypse I might want a thousand pages of post-pandemic horror from the 1970s. We all have our contingencies.

The Japanese have a word for this, of course: tsundoku, the practice of buying books and letting them pile up unread. It sounds delicate, almost noble, like a disciplined art form rather than a slow accumulation of war histories and guilt. But it captures something true.

I don’t buy books simply to read them—I buy them to become the kind of person who would.

Each purchase is an act of projected selfhood, a small ritual of aspiration. That I rarely follow through is beside the point. After all, the ideal version of me—multilingual, well-read, effortlessly erudite—needs a library. I’m just doing the groundwork.

And so, the shelves grow heavier with what I’ve come to think of as the silent majority: the untouched books. They sit quietly, sometimes for years, exuding a passive-aggressive air of academic disappointment. Guilt piles up. I imagine them whispering to each other at night: “He bought me in a frenzy of enthusiasm after watching a documentary on Syriac mysticism and never even cracked the spine.” “He said he was going to teach himself Russian.” “He shelved Music in the Castle of Heaven next to the memoirs of Napoleon—he’s a madman!”

Moving them, I feel less like a man and more like a reluctant museum curator. I know I could cull the collection. I know I won’t. To part with them would be to admit that I will never become the man who reads Thrasyllan Platonism for fun, or the one who actually finishes Eros and Magic in the Renaissance instead of googling “was Culianu murdered?” (yes, and probably for knowing too much). I promise myself, yet again, that someday I’ll put in a concerted effort to learn the basics of Egyptian hieroglyphics.

No, they will all come with me. Even the duplicates—both identical copies of Suetonius. Even the partly burnt copy of Horace’s Odes and Epodes. Even the wine dictionary, though the stain on page 203 has rendered “Chassagne-Montrachet” illegible. Even Stalin.

Because here’s the truth: buying books, especially unread ones, isn’t about information. It’s about orientation. Each spine is a compass point toward a possible self—a thinker, a writer, a mystic, a man who knows the difference between Romanesque and Gothic blind arcading without checking Wikipedia.

I am not that man. But I own his library.

And God help the movers.

Contributed by

– Jonathan Bennett