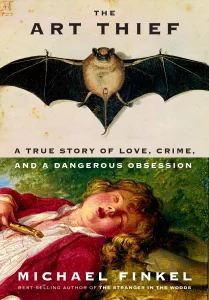

The Art Thief by Michael Finkel : A Book Review

The Art Thief by Michael Finkel : A Book Review

This year, 2023, has seen the publication of Michael Finkel’s The Art Thief, a riveting true account of the escapades of Stephane Breitwieser, a native of Alsace, and probably the most prolific art thief in history who, until he was caught, tried, and punished, stole art from museums in France, Belgium, and Switzerland, for the better part of a decade, with the active help of his girlfriend. He kept his ill-gotten hoard of art treasures, like Smaug the dragon in Tolkien’s The Hobbit, in his own cave, two rooms of an apartment in the attic of his mother’s house, entry to which she was apparently denied by her own son. In that secret hideaway was a treasure trove consisting of stolen oil paintings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, tapestries, flintlock pistols, silver cups, bowls, chalices, a famous ivory statue of Adam embracing Eve in the Garden of Eden, and even a four-foot tall wooden statue of the Virgin Mary from a church, anything of value that took his fancy, in a haul alleged to have been valued at up to $2 billion. As an introduction to his narrative, Finkel provides the reader with an artist’s rendering in twin line drawings of the rooms’ probable contents, an art gallery of his very own.

The gripping story of this crime spree has been exhaustively researched over several years by its author, who interviewed police, art experts, and psychologists for his study, and provides in minute detail the modus operandi of the thief for many of his robberies, his success attributable in large measure to poor museum security and cunning sleight of hand on the part of the thief himself. When Breitwieser is finally caught, the story is far from over, for when police visit the house following his confession of guilt, its attic rooms are found to be empty.

Readers trying to make sense of what happened next must examine the motivation of the culprit or culprits who removed the contents while Breitwieser himself was in police custody, and come to terms with the sentences eventually handed down to those involved from the outset. Finkel maintains suspense throughout, yet one hostile reviewer has glibly dismissed his effort as productive of a “popcorn flick of a book” and the thief himself as unworthy of the attention extended him. Such a judgement does not do justice to the story or its author, nor does this same critic’s scornful claim that Finkel has sympathetically portrayed Breitwieser, despite his criminality, as a misunderstood “romantic hero.”

The truth is that Breitwieser is an enigma. Now in his sixties, he was bullied as a child, a social outcast who disliked parties, video games, and social media, preferring to seek solitary solace in collecting stamps, coins, and old postcards. “I was the opposite of everyone” he says. He explained his love of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian artifacts by admitting “I took refuge in the past.” He was, says Finkel, “born in the wrong century.” An only child, his parents were distant from him, his rich father harsh and judgemental, and after he abandoned his family, divorce was inevitable. His mother, a nurse, was reduced to penury. She drew shocked comment when, years later, at her son’s trial, she publicly announced “I hate my son.” Breitwieser never worked steadily, only at menial jobs, and never for long, preferring to live off welfare benefits, generous gifts from his grandparents, and rent-free accommodation provided by his mother, who kept her distance from him. He was considered by several familiar with him as both immature and spoiled, yet his dysfunctional life began years before adulthood.

Breitwieser stole because he could. He wanted to surround himself with beauty, to “gorge himself on it.” He was an amateur devotee of aesthetics, the study of beauty, frequently feeling overcome with a “coup de coeur” whenever he saw beauty in a work of art, which he then longed to possess. He was also cunningly resourceful as a thief, with lightning-quick reflexes, and brazen charm, knowing how to obtain the object for himself. He justified this compulsion by claiming that museums “imprisoned” art, while he “liberated” it. At no point did he appear to recognize that this is a profoundly selfish attitude, nor did he ever express remorse for his crimes or for the harm these caused. In fact, as Finkel himself observes, the story of art has been seen by some as “a story of stealing”: Greece still claims the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum were stolen; Napoleon helped himself to Egyptian antiquities in 1798.

This is not by any means to diminish the iniquity of Breitwieser’s thievery. Yet those who would dismiss Finkel’s book as merely a sensational potboiler should pay more attention to the author’s subtlety. He begins and ends his narrative with references to Georg Petel’s seventeenth-century ivory sculpture of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, stolen from the Rubens House museum in Antwerp.

In Petel’s depiction of Adam and Eve, the couple is physically close enough to one another to touch, having eyes only for one another. They appear not to see the snake Satan entwined around the tree beside them. Intentionally or otherwise, the author, by way of the sculpture, reminds us of the perils of temptation that the Genesis story encapsulates for us. Disobedience to God’s commandments results in the expulsion of both Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, the loss of Paradise, the Fall of Man, and the coming of sin into the world. There, in his very bedroom, Petel’s sculpture itself was for years an unheeded warning to the unrepentant art thief as he gloated over and congratulated himself on his cleverness. The story behind the sculpture is profoundly moral, as is the inevitable fall of Breitwieser himself.

After he had served his time, and become temporarily reconciled with his father, the hapless thief could not overcome the temptation to steal again, again, and again. He is compulsively addicted to his obsession to possess. He loses his father’s sympathy; his girlfriend no longer wants a part of him. He is arrested and jailed again and again, often for petty theft. The world loses its interest in his celebrity status, and he cannot be gainfully employed on account of his criminal record and recidivist status. He is loveless, friendless, alone, ruined. Too late has come self-knowledge. “I was a master of the universe,” he confesses. “Now I’m nothing.”

The Art Thief by Michael Finkel : A Book Review

The Art Thief by Michael Finkel : A Book Review