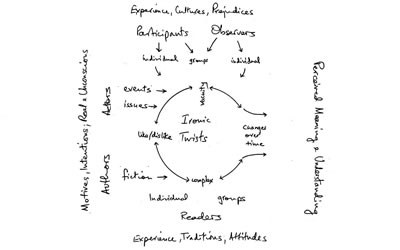

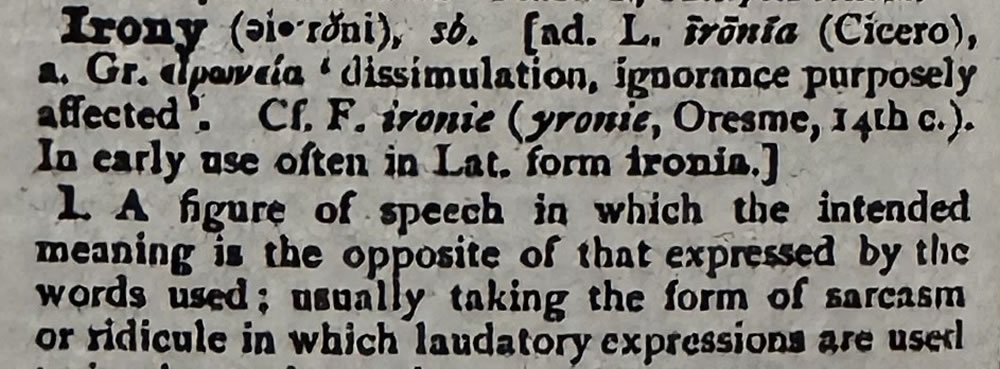

“It’s as clear as mud.” Since mud is not clear, the speaker cannot mean what he says. (Let us assume he is male). In fact, he means that what he has heard or read is unclear. Very unclear. He says the opposite of what he means to emphasize his difficulty in understanding the communication. His comment is ironic, as are “as friendly as a rattlesnake” or “about as much fun as a root canal,” neither of which can be said to induce pleasure. The opposite is intended, and surprise is unexpected. That, of course, is the nature of surprise. It is how it is defined.

These examples show irony at its simplest. Irony’s essential characteristic is its oppositional, unexpected nature. If it rains on your wedding day, this is an unfortunate coincidence, perhaps unexpected, but it is not ironic. The word derives from the Greek eironeia or ‘simulated ignorance.’ Something in the speaker or writer’s tone, or in the context of the statement or circumstance alerts the attentive hearer or reader to the fact that the utterance is not to be taken at face value. When the intended meaning is grasped, usually instantly, as in the first three examples above, a state of ‘secret intimacy’ is said to exist between the initial speaker and its recipient, the listener. The greater the degree of intimacy, the greater the delight in penetrating the apparent meaning to understand what is intended. Here are some more examples:

When, in Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the mariner is becalmed on his ship in the ocean in the tropics, thirsty for want of a drink of water, he is a victim of irony: ‘Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink’. He cannot relieve his thirst by drinking salt.

The RMS Titanic, billed as ‘unsinkable,’ hits an iceberg on its maiden voyage and sinks.

King Duncan in Shakespeare’s Macbeth is appalled at the Thane of Cawdor’s treachery. “He was a gentleman on whom I built an absolute trust,” the king confides to Macbeth, blissfully unaware of Macbeth’s own intention to murder him when the opportunity presents itself. The audience, however, does know of it. This is dramatic irony.

In another case of dramatic irony, in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, Oedipus angrily denies that he is his father’s murderer, but he does not know who his father is. The audience, however, knows Oedipus has in fact killed a man unknown to him who would not let him pass at a crossroad.

In Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Middle Earth is saved not by triumphant armies of the righteous, but by a humble modest hobbit whose success and bravery are quite unexpected.

To the Christian believer, God Almighty takes vulnerable human form, born humbly in a manger, then living as an itinerant teacher to deliver the Good News of mankind’s salvation before submitting Himself to an unjustified painful death before His triumphant Resurrection.

In O. Henry’s The Gift of the Magi, a poor husband and wife each decide to buy the other a Christmas present. The husband receives from his wife an expensive chain for the watch he sold to buy his wife some decorative combs, while she had sold her hair to buy the chain for him.

In Guy de Maupassant’s The Necklace, a poor woman borrows a necklace from a rich friend only to lose it. She borrows money to pay for its replacement, too ashamed to let her friend know of the loss. She and her husband work for ten years to pay off the loan, only to discover belatedly that the lost necklace was made of “paste,” and was consequently valueless.

The animals of George Orwell’s Animal Farm are brainwashed into thinking “Four legs good, two legs bad,” in order to demonize their former, two-legged, keepers, Men. Yet they lack the intelligence to see that they have been had, when their new overlords, the pigs, begin to walk about on two legs, and train them to repeat robotically the new commandment: “Four legs good, two legs better!” Orwell uses irony to satirize Soviet historical revisionism.

When the boys in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies are rescued at the end of the novel, their rescuer, a naval officer, thinks they have been having harmless fun on the island. “I know,” he says, “Jolly good show. Like The Coral Island.” He doesn’t “know” what has been going on, but the reader does. The irony here is that there is no happy ending, as there is in R.M. Ballantyne’s children’s classic The Coral Island. The boys on this island resorted to fear and superstition, threats and brute force, and, horribly, even murder, during their stay.

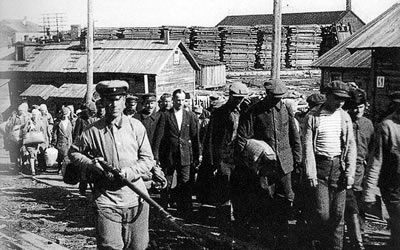

During a peaceful march in St. Petersburg in 1905, led by Father Gapon, an Orthodox priest, unarmed demonstrators, bearing sacred icons and portraits of the Tsar, and singing “God save the Tsar,” were shot by the Tsarist Imperial Guard. Some 100 demonstrators were murdered.

The Dutch evangelist Corrie ten Boom, interned with her sister in a Nazi concentration camp for hiding Jews wanted for extermination, hears her sister, upon seeing a Nazi guard bludgeon a helpless old Jewish woman to the ground with his rifle butt, cry out, “Oh, the poor man!” Many readers will think her sister’s sympathy misdirected: it is the guard’s victim who needs the sympathy, surely? Yes, says Corrie, of course, but the armed Nazi’s situation is worse: how twisted must the man be to assault so brutally a defenceless old woman due to die soon at the hands of her evil tormentors? The irony of the pronouncement by Corrie’s sister, who died in Ravensbruck, is designed to focus attention on the endangered soul of the vicious guard…

There are, of course, many more instances of irony to be found in literature, as in life. Readers are welcome to contribute their own choices of irony to the ongoing discussion. Irony is not always, or even easily, understood. What baffles the uninitiated may privilege an elite of the knowledgeable, who may relish their status as “secret intimates” of the ironist, a relationship that the unenlightened cannot share, a characteristic that will be further explained in an upcoming issue of The Ironist.