The Russian writer, dissident, and Nobel Prize for Literature laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1917-2008) was an outspoken critic of communism in what was then called the Soviet Union, and was imprisoned in the Siberian gulag for eight years for critical comments he made of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin in a private letter to a friend. His later writings, including One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch and The Gulag Archipelago, were based on the ill treatment he and countless other innocent victims of Soviet repression suffered as a result of their alleged crimes. Disillusioned with the false promises of an allegedly ‘classless’ society, he became a Christian, and until his death years after his release, he continued to point out to authorities the yawning disparity between the promise of official propaganda in his native land and the reality of life in Russia. Yet both he and other victims of injustice have testified in print to moments of revelation that brought hope to them in their pained and silent suffering.

Prisoners at Solovki; credit Peter Lowe, Pushkin House, 2020

In a ‘prose poem’ called ‘The Elm Log,’ the author provides readers with a short personal narrative of an epiphany that occurred to him and his unnamed workmates when they came across an elm log from a tree they had chopped down the year before. Most of the logs from the downed tree, he tells us, were “thrown on to barges and wagons,” but one remained at their feet. It had not given up the struggle for life. “A fresh green shoot had sprouted from it with promise of a thick, leafy branch, or even a whole new elm tree.” The men “placed the log on the sawing-horse, as though on an executioner’s block, but we could not bring ourselves to bite into it with our saw. How could we? That log,” he says, “cherished life as dearly as we did; indeed, its urge to live was even stronger than ours.”

Solzhenitsyn does not tell us when and where this event took place, as this does not matter. The example of the persistence of a natural force in the shadow of death was inspiration enough for him to recall it with astonishment and reverence years later.

Something similar happened to French-born heroine Odette Samson, (also known as Odette Churchill and Odette Hallowes) during her imprisonment in the Ravensbruck extermination camp for women north of Berlin in the Second World War. Sent to Occupied France in November 1942 as an agent for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) with the given code name ‘Lise,’ Odette had a passionate desire to help liberate her native land from German enslavement. She was captured and interned as a spy. Repeatedly tortured by the Gestapo, she remained defiant. Despite having all her toenails pulled out one by one, she never revealed secret information entrusted to her, and was sentenced to death, and then sent to Ravensbruck. In his biography Code Name Lise, the American author Larry Loftis tells what happened when Odette found a leaf “blown into her cell by a kindly breeze.” As there were no trees in the extermination camp, this was highly unusual. Loftis’ narrative continues: “Light permitted the intrusion of a solitary example of something — God, creation, life. In a small way, it gave her a glimmer of hope.” Odette survived the death camp, was honoured both by Britain and France at war’s end for her heroism, and lived to the age of 82 before her death in 1995. Such seemingly trivial events had an enormous effect on the spirit of both of these individuals. What they each saw was a symbol of something bigger than themselves that rendered their own plight easier to manage.

Ravensbrück Crematorium ovens, credit our Soviet allies who liberated the camp, 1945

A third example, in this case the importance of routine, is conveyed in Sir Ernest Shackleton’s account of the loss of his ship Endurance, crushed by ice in the frigid waters of Antarctica in November 1915, a disaster that left its crew stranded on the shifting ice floes of the Weddell Sea, with limited supplies, only makeshift shelter, no method for communicating their distress to rescuers, and with no way home, and the imminence of death apparent to them all. In his book South: The Endurance Expedition, Shackleton describes the scene before him shortly before Endurance’s sinking. His men are clustered around the cook, telling him how they liked their tea, then being prepared for them. “It occurred to me at the time,” says our author, “that the incident had psychological interest. Here were men, their home crushed, the camp pitched on the unstable floes, calmly attending to the details of existence and giving their attention to such trifles as the strength of a brew of tea.”

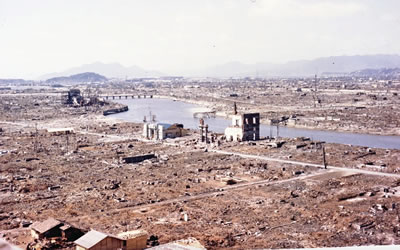

Final sinking of the Endurance, Royal Geographical Society, November 1915

Such trifles: a log, a leaf, a cup of tea. But what trifles! The incident invites Shackleton to reflect: “Man fights against the giant forces of Nature in a spirit of humility. One has a sense of dependence on the higher Power.”

Shackleton was knighted for his own rescue of all of his men following a death-defying trip with five of his crew, rowing across 800 miles of sea ice from Elephant Island to South Georgia, where he was able to summon help for the remaining twenty-three members of the doomed Endurance expedition. His courage and strength of will, complemented by the trust his capable and imperturbable men placed in their indomitable ‘Boss’ surely merit the name of their own human endurance.